Some people in a ‘normal’ weight range are more likely to die than those in the overweight category, say researchers

People who are overweight or obese are at no greater risk of dying than those within the ‘normal’ weight range based on their BMI, a study presented at a diabetes conference showed.

Danish researchers found those who were underweight or at the lower end of the normal range were actually more likely to die.

BMI (body mass index) is a weight-to-height measurement used to assess if someone is a healthy size. A score of 18.5-25 is generally considered normal, or healthy. Those below 18.5 are categorised underweight, 25-30 is overweight and above 30 is obese.

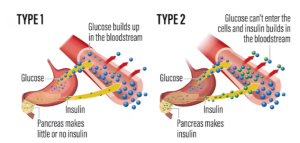

“Both underweight and obesity are major global health challenges,” says Sigrid Bjerge Gribsholt, of the Steno Diabetes Center Aarhus, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark, who led the research. “Obesity may disrupt the body’s metabolism, weaken the immune system and lead to diseases like type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and up to 15 different cancers, while underweight is tied to malnutrition, weakened immunity and nutrient deficiencies.

“There are conflicting findings about the BMI range linked to lowest mortality. It was once thought to be 20 to 25 but it may be shifting upwards over time owing to medical advances and improvements in general health.”

The study of more than 85,000 people, presented at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Vienna, found those in the 25-30 range were no more likely to die within five years of follow-up than those in the 22.5-25 range. Those who were underweight were almost three times more likely to have died than those towards the top end of the healthy range, while those at 18.5 were twice as likely to die and those in the 20 – 22.5 range – in the middle of the supposedly healthy weight range – were 27 per cent more likely to die.

By contrast, those considered overweight or obese – which researchers said could be considered metabolically healthy of “fat but fit” – did not see an increased likelihood of death.

However, those with a BMI of 35-40 saw an increased risk of death of 23 per cent. A similar pattern was seen regardless of age, sex and education.

Dr Gribsholt says: “One possible reason for the results is reverse causation: some people may lose weight because of an underlying illness. In those cases, it is the illness, not the low weight itself, that increases the risk of death, which can make it look like having a higher BMI is protective.

“Since our data came from people who were having scans for health reasons, we cannot completely rule this out.

“It is also possible that people with higher BMI who live longer – most of the people we studied were elderly – may have certain protective traits that influence the results.

“Still, in line with earlier research, we found that people who are in the underweight range face a much higher risk of death.”

Prof Bruun cautioned that BMI is not the only indicator of unhealthy levels of fat. Where you store fat can be more important.

“Other important factors include how the fat is distributed. Visceral fat – fat that is very metabolically active and stored deep within the abdomen, wrapped around the organs – secretes compounds that adversely affect metabolic health.

“As a result, an individual who has a BMI of 35 and is apple-shaped – the excess fat is around their abdomen – may have type 2 diabetes or high blood pressure, while another individual with the same BMI may free of these problems because the excess fat is on their hips, buttocks and thighs.

“It is clear that the treatment of obesity should be personalised to take into account factors such as fat distribution and the presence of conditions such as type 2 diabetes when setting a target weight.”

*thenationalnews